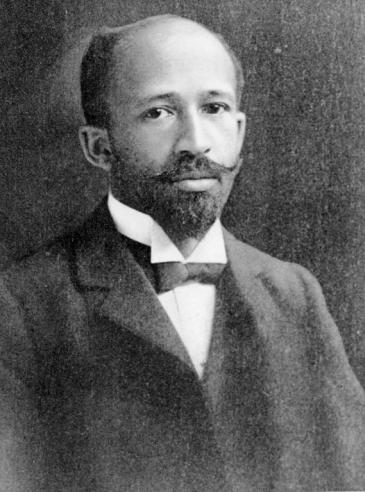

W. E. B. Du Bois and the NAACP

W. E. B. Du Bois was the first black recipient of a Ph.D. from Harvard University. In The Souls of Black Folks, published in 1903, he argued for "manly" and "ceaseless agitation and insistent demand for equality." He demanded a curriculum of liberation for Black people, not subordination, which is how he described the Hampton/Tuskegee approach — known as “accommodation”--espoused by Booker T. Washington. Du Bois rejected accommodation as the best response to the stark racial segregation which enveloped America. Jim Crow had been concretized by Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision that sanctioned the principle of "separate but equal" facilities for African Americans and whites.

Du Bois became director of publicity and research for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909. The legal arm of the NAACP led the campaign to end segregation altogether, but it first targeted inequality in education. It helped win the admission of a black student to the University of Maryland Law School because that state did not have such an institution for Black students. Virginia and other southern states immediately adopted a policy of giving scholarships to black students to attend professional and graduate schools outside the state. That practice was eventually rejected by the U.S. Supreme Court, in December 1938, and Richmond editor Virginius Dabney said the decision "severely jolted" the South's educational system.

In October 1938 the NAACP filed suit over the fact that Black teachers in Norfolk were paid less than their white counterparts. In Alston v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, a federal court ruled that this discrimination was based on race alone and thus violated the "equal protection" clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution. The decision was met with delays, evasions, adoption of subjective criteria for evaluating teachers, and other methods of resistance, so that Black teachers went from being paid one-half of white salaries to two-thirds, but not to full equality until 1952.