Turning Point: World War II

P. B. Young, editor of the Norfolk Journal and Guide, a black newspaper, spoke from the heart when he told white liberals, "Help us get some of the blessings of democracy here at home before you jump on the 'free other peoples' band wagon and tell us to go forth and die in a foreign land." First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt said, "The nation cannot expect the colored people to feel that the U.S. is worth defending if they continue to be treated as they are treated now." In spite of these contradictions, black Virginians were eager to join the armed forces. At first the military proved reluctant to enlist them or else assigned them to menial roles. But in time the army and navy increased opportunities for black men and women, and Richmond's Dimmeline Booth became one of the first black marines in 1943.

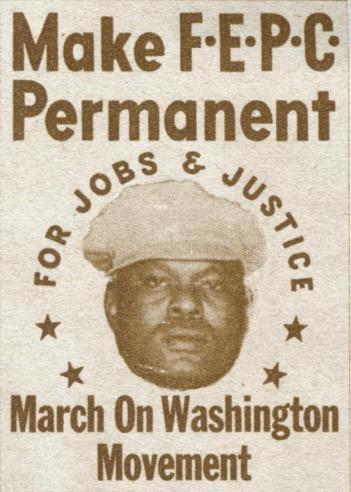

In 1940, 19 percent of black men were unemployed, and most black families lived in poverty. The huge defense buildup that began with the fall of France in June 1940 ended the Great Depression and brought back prosperity. But black Americans were denied an equal share. Using the slogan "We loyal Negro-American citizens demand the right to work and fight for our country," black Americans threatened to march on Washington to demand these rights. They forced President Franklin Roosevelt to issue Executive Order #8802, which opened government jobs and defense contract work to black Americans on the basis of equal pay for equal work. It was the first presidential action against discrimination since Reconstruction.

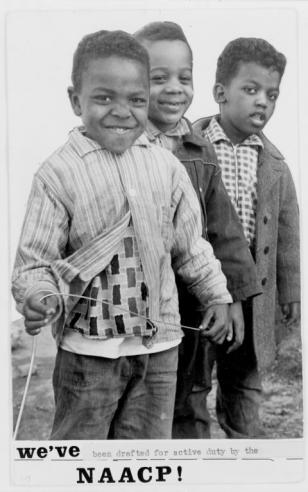

The war years were tumultuous, but black men and women sensed that out of this ferment change might come. After the bleak racism of the 1920s and the economic disaster of the 1930s, there was hope. Black newspapers conceived the "Double V" campaign—victory over both America's enemies abroad and over Jim Crow segregation at home. In this hopeful atmosphere the NAACP increased the percentage of registered black voters in the South from 2 to 12 percent. Membership in the NAACP itself increased from 18,000 before the war to nearly 500,000 at its close.

As the Cold War began, America could not claim to be the defender of freedom and democracy when it practiced segregation and discrimination at home. President Harry Truman fully desegregated the armed forces in 1948, and a government report of 1947 called To Secure These Rights called for "the elimination of segregation from . . . American life." The stage was set for the civil rights movement.